Chapter three begins with a great metaphor to help better understand was qualitative research actually is. Think of qualitative research as an intricate fabric composed of minute threads, many colors, different textures and various blends of materials.

Study 42 Chapter 3 - The Humanist Approach flashcards from Anjali K. Human Behavior: A Multidimensional Approach. Chapter 3: The Biological Person. An Integrative Approach for Understanding the Intersection of Interior (Proximal) Biological Health and Illness and Exterior (Distal) Environmental Factors.

Some terms brought up to further research are constructivist, interpretivist, feminist, and postmodernist, all terms frequently used in qualitative research. (p. 42)

Characteristics of Qualitative Research: two great books to reference for different sets of definitions are listed on p 43, SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research and Morse and Richards.

Qualitative research begins with assumptions and the use of interpretive/theoretical frameworks that inform the study of research problems addressing the meanings of individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem. To study this problem, qualitative researchers use an emerging qualitative approach to inquiry, the collection of data in a natural setting sensitive to the people and places under study, and data analysis that is both inductive and deductive and establishes patterns and themes. The final written report or presentation included voices of participants, the reflexivity of the researcher, a complex description and interpretation of the problem and its contribution to the literature or a call for change.

The author states that it is easier to move from a general definition to specific characteristics found in qualitative research.

Pages 45-47 explores common characteristics of qualitative research and the table 3.1 on page 46 provides three introductory qualitative research books.

Common Characteristics:

Study 42 Chapter 3 - The Humanist Approach flashcards from Anjali K. Human Behavior: A Multidimensional Approach. Chapter 3: The Biological Person. An Integrative Approach for Understanding the Intersection of Interior (Proximal) Biological Health and Illness and Exterior (Distal) Environmental Factors.

Some terms brought up to further research are constructivist, interpretivist, feminist, and postmodernist, all terms frequently used in qualitative research. (p. 42)

Characteristics of Qualitative Research: two great books to reference for different sets of definitions are listed on p 43, SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research and Morse and Richards.

Qualitative research begins with assumptions and the use of interpretive/theoretical frameworks that inform the study of research problems addressing the meanings of individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem. To study this problem, qualitative researchers use an emerging qualitative approach to inquiry, the collection of data in a natural setting sensitive to the people and places under study, and data analysis that is both inductive and deductive and establishes patterns and themes. The final written report or presentation included voices of participants, the reflexivity of the researcher, a complex description and interpretation of the problem and its contribution to the literature or a call for change.

The author states that it is easier to move from a general definition to specific characteristics found in qualitative research.

Pages 45-47 explores common characteristics of qualitative research and the table 3.1 on page 46 provides three introductory qualitative research books.

Common Characteristics:

- Natural setting

- Researcher as a key instrument

- Multiple methods

- Complex reasoning

- Participants meanings

- Emergent design

- Reflexivity

- Holistic account

When to use qualitative research: we conduct qualitative research because a problem or issue needs to be EXPLORED. We use qualitative research for a topic with many variables that need to be explored in depth. (p 48)

Page 49 dicussed what qualitative research studies require of us; commitment to extensive time in the field, engage in complex, time-consuming processes of data analysis, writing long passages and participate in a form of social and human science research that does not have firm guidelines.

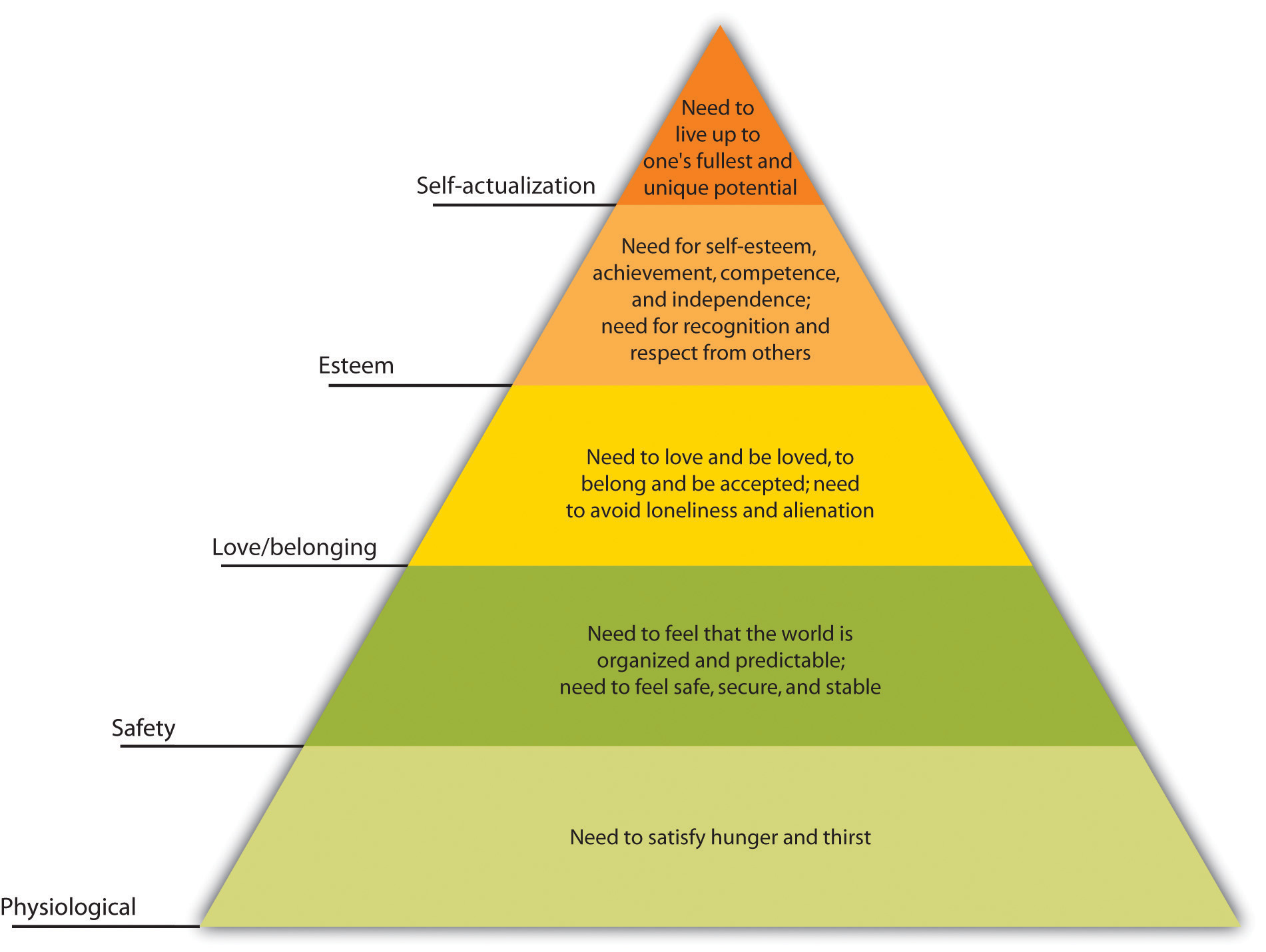

Humanist Definition

Essentially, research design can be defined as the plan for conducting the study. It is important to note that there is absolutely no agreed upon structure for how to design a qualitative study, but that there are paths that one can take to determine the appropriate format. Examples of how to design a qualitative study can be found on page 50 of this chapter and include reading a study (Weis & Fine, 2000); understanding the broader issues (Morse & Richards, 2002); and guidance from a how to book (Hatch, 2002). Creswell, however, supplies his own method that consists of three components that guide section. These are: preliminary considerations prior to beginning a study; the steps engaged in during the study; and elements that flow through all the phases of research.

In the first section, preliminary considerations, Creswell states that research, whether quantitative or qualitative, generally follows the scientific method. For a quick refresher, the scientific method consists of a statement of the problem, hypotheses, data collection, results, and discussions. In this section, the idea of the methodological congruence (Morse & Richards, 2002) is introduced. When designing a research study, the purpose, questions, and methods of research should all be interconnected and interrelated; the design should be a cohesive whole instead of fragmented pieces.

Qualitative research will also include a literature review after a statement of the problem to help flesh out why it is a problem and what has been researched previously. Creswell provides an excellent explanation of how a literature review can work depending on the study design on pages 50 and 51.

Lastly, when beginning the research design, it is important to consider yourself as a researcher. Your personal history, assumptions, and interests will help situate yourself in your own research and the larger body of research previously conducted on your topic (p. 51).

The next section details steps in the process of designing a qualitative study. This section is extremely important and should be considered a ‘must-read' for everyone in the class (pages 51 to 53). Here are some key points:

- Keep research questions open-ended; first speak with individuals and then design your questions for the interview process; allow your questions to evolve and become more refined

- There are four basic sources of qualitative information: interviews, observations, documents, and audio-visual materials

- There are 'no ‘right' stories, only multiple stories' (p. 52).

Creswell also goes into great detail discussing the method of analysing data once it's been collected. This can be found on page 52 as well, and should be read.

Validating data once it's been collected and organized is also extremely important. Data can be confirmed via triangulation or peer review (p. 53). Various standards have been determined for validating data in Howe & Eisenhardt (1990), Lincoln (1995), and Marshall & Rossman (2010), however, Creswell has created his own list. This list, which begins on page 53 and continues through to page 55, contains a lot of excellent information to help ensure a rigorous study through data collection, researcher assumptions, inquiry method, study focus or concept, and data analysis.

Final considerations for designing a qualitative study are two-fold: ensuring that a narrative comes out of the data collection and analysis (p. 55) and ethical considerations (p. 56 onwards). Researchers must be sensitive to participants, sites, stakeholders, and publishers of their research. Creswell cites Weis & Fine (2000) as a resource for more information on the topic, and also provides his own preferred approach. This approach can be found on pages 58 to 59, Table 3.2. This table is essential for understanding potential ethical issues and solutions at all stages of the research process. It is also important to seek research approval from various boards and societies, and to remember to not conduct 'the worst study of all time', as discussed in the first class.

While the author stresses on page 61 that there is no set format for what the final written product of a qualitative study should look like, he does provide four examples of how to structure a proposal. This is particularly of interest to us as we will be writing our own proposals for this course.

Chapter 3: The Humanist Approach Suggests

The first proposal format presented in the chapter is the author's own preferred format- a traditional approach which includes sections for the introduction, procedures, ethical issues, expected outcomes, etc. (see Example 3.1 on page 61).

The next format highlighted on page 62 is very similar, but puts a focus on advocacy for the group of individuals that is being studied (see Example 3.2 for the full structure of the 'transformative' format).

Page 63 discusses the 'Theoretical/Interpretive' format and as the name suggests, this format is best for qualitative studies that use a theoretical lens. This format has a few unique sections including the ethical and political considerations of the author as well as a personal biography (see full proposal layout on page 63).

The last proposal format is organized around 9 arguments that the researcher needs to align. The author says that these 9 points are the most important to include in a proposal and touch on topics like purpose, data collection, analysis, ethics, etc. (see Example 2.4 on page 64).

Lastly, the author explains that these format examples only cover a qualitative research proposal. When writing up a complete qualitative study, many other sections will need to be included, and it's more difficult to create a standardized format.

Humanist Approach Examples

Courtney Kurysh, Sadia Mehmood, and Lauren Wolman